Zohran Mamdani's “War on Prices”

The NYC Mayoral candidate's pricing policies would bring a high efficiency cost

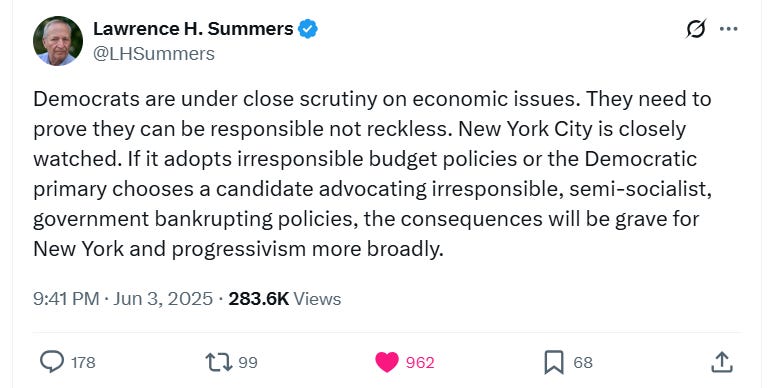

I hadn’t been following the New York City mayoral race at all until I saw the tweet below from Larry Summers. Larry sounded worried about the political consequences of someone in the city’s Democratic mayoral primary, who he said was advocating “irresponsible, semi-socialist, government bankrupting policies.”

That individual is New York State Assembly member Zohran Mamdani, a democratic socialist, who is now surging as the clear second-favorite behind Andrew Cuomo. Interestingly, Mamdani’s campaign is centered on aggressive measures to lower the cost of living. Across rental housing, labour markets, transit, childcare, and even groceries, he proposes to hold or push prices far below market‐clearing levels (or, in the case of wages, well above them) or else expand government provision of “free” stuff financed ultimately by taxpayers.

He is, quite simply, the political embodiment of the faulty economic thinking we warned about in The War on Prices. While there’s plenty of other things to dislike about his platform—not least uncertainty over how he plans to raise revenue to fund his promises, and his permissive approach to crime and disorder, I thought it worth running through his cost of living plans using an economic lens.

Rental Housing

Mamdani wants to tighten and expand rent control. Of course, New York City already has “rent stabilization” covering just under a million apartments. Each year, the Rent Guidelines Board (whose members the Mayor appoints) sets the allowable annual rent increases for these units. Recently, under Mayor Adams, the RGB approved significant nominal hikes, though given recent high inflation, these increases have still left regulated rents lagging behind surging market rates.

According to the NYC Rent Guidelines Board, the median contract rent for rent-stabilized tenants was $1,500 per month, lower than the median $2,000 market rent contract. For newly registered rent controlled apartments, there is a discount too: a $3,105 median compared with a $3,397 median asking rent price city‑wide today. Mamdani pledges to press his Rent Guidelines Board appointees, though, for a 0 percent rent increase—an outright freeze—for rent-stabilized properties for four years. That edict would stretch those gaps still further, gradually turning the wedge into a canyon.

Such a freeze would inevitably deepen existing shortages of regulated apartments. It’s true that in the short-run, the supply of these properties is fairly inelastic anyway—it's difficult for landlords to shift apartments out of stabilization. Currently, a tenant in a rent-stabilized apartment has near-perpetual rights to renew leases. Landlords can regain possession or deregulate only via narrowly defined pathways, primarily through giving up certain tax benefits, undertaking significant renovation or demolition, or by reclaiming a single unit for personal occupancy.

Some do, of course, and more will with a rent freeze—there was a net estimated loss of 4,170 rent-stabilized units in 2023, for example. So holding prices further below market rates would reduce the rent-stabilized supply to some extent. And, certainly, faced with long-term real-income erosion due to a prolonged price freeze, more landlords might abandon properties or else allow buildings to deteriorate in quality over time.

But the bigger welfare loss arises here through misallocation—people being in the wrong properties relative to their needs. As regulated rents drift further below market prices, quantity demanded inevitably increases. Already, New York’s 2023 Housing & Vacancy Survey found a mere 0.98 percent vacancy rate among rent-stabilized units—a historic low, far below the 5 percent threshold the city defines as a "housing emergency."

New tenants seeking rent-stabilized apartments will thus endure higher search and queuing costs with a rent price freeze. Incumbent tenants will remain in apartments even longer than their housing needs warrant, fueling an informal market in succession rights. Simultaneously, landlords' declining net operating income will further discourage critical investments in maintenance like boilers, roofs, and plumbing, exacerbating the deterioration of housing quality. There’s a reason why, already, it’s rent-stabilized apartments that face disproportionate complaints about rodents, leaks, cracks and heating in New York City.

Moreover, with regulated supply fairly fixed in the short-run, excess demand will inevitably spill over into the unregulated market, pushing up rents for market-rate units. Consequently, rent-stabilized tenants—the insiders—gain significantly from Mamdani’s freeze, while newcomers, mobile workers, and younger renters face worsening affordability.

What about the impact on any new building of rentable accommodation? Currently, newly constructed apartments aren't subject to rent stabilization unless developers voluntarily opt-in through specific incentive programs, so we shouldn’t expect a huge impact.

Some observers have been heartened by Mamdani's statements favoring zoning reform too—acknowledging, for instance, that density restrictions around transit hubs, parking minimums, and restrictive zoning codes constrain private housing supply. Deregulating here could further encourage development of market rental properties.

But Mamdani’s broader regulatory approach threatens to undermine all these supply-side gains. As the Manhattan Institute’s Reihan Salam has said, layering private-sector development with restrictive measures such as mandated affordability quotas, prevailing wage requirements, and "good-cause" eviction laws, as Mamdani desires, significantly diminishes the profitability of new private rental construction. These policies invariably discourage investment and suppress the total supply of housing.

Furthermore, investors are likely to perceive heightened political risks from Mamdani's administration on the rent control front. He openly champions building 200,000 city-financed, rent-stabilized apartments, significantly enlarging the size of the rent-regulated housing stock. Given his aggressive stance on expanding controls through government building, it’s entirely plausible he might also pursue regulatory means or lobby Albany to pull additional market-rate rentals into the rent stabilization regime, despite current state restrictions preventing this.

Any regulatory uncertainty will push real estate investors to demand higher returns or shift their capital to less risky environments like the rapidly growing Sunbelt cities. Over time, New York will see fewer new rental projects, increased condominium conversions, and greater capital flight—further reinforcing long-term housing scarcity.

While Mamdani portrays his rent freeze as a vital measure to provide immediate cost-of-living relief after high inflation, the economic consequences of rent controls are highly negative in the long run. His rent control policies will exacerbate existing shortages, lower apartment quality, discourage essential investment, and ultimately lead to even less affordability across the city's entire housing market.

Minimum Wage

Mamdani is proposing a drastic rise in New York City’s minimum wage. Branded as “$30 by ’30,” his plan aims to nearly double today’s $16.50-per-hour NYC minimum wage, incrementally pushing it up to $30 by 2030. Thereafter, Mamdani proposes indexing this wage floor annually to either inflation or productivity growth, whichever is higher.

Yet there’s a critical legal hurdle to this ambitious plan: New York City currently lacks legal authority to set a separate local minimum wage beyond the state-mandated floor. Mamdani acknowledges this legal constraint but argues there are “legitimate routes” around this preemption. He says he'd collaborate with the City Council to pass a local law and simultaneously lobby Albany to permit NYC-specific minimum wage regulation.

Let’s assume, optimistically for Mamdani, that he succeeds in gaining this legal authority. A $30 per hour minimum wage for New York, even by 2030, would be a dramatic uplift, increasing the gap between the marginal product of labor for many lower-paid workers and the regulated wage.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data reveals that a $30 hourly wage floor would substantially exceed average hourly wages in many sectors across the New York metropolitan region today, including personal care and service ($22.07/hour), farming, fishing and forestry ($22.63), building and maintenance ($22.74), production occupations ($25.57), food preparation ($21.75), and healthcare support ($20.23). Collectively, these sectors employ approximately one-quarter of the metropolitan region's workforce.

Numerous other industries currently pay average wages that will likely be only slightly above the proposed $30 threshold by 2030 too, suggesting a huge fraction of jobs would become uneconomical without productivity improvements. While New York City undoubtedly has higher productivity levels than most other areas of the country and so can bear a higher wage floor, this wage regulation would thus still be very distortionary.

Contrary to progressive opinion, most academic assessments of state and local minimum wage hikes find disemployment effects like fewer jobs and employee hours, especially when the increases in the wage floor are large. The Congressional Budget Office estimated a federal $17 minimum wage by 2029 could eliminate up to 2 million jobs nationally. Given Mamdani’s proposed floor is much higher, even adjusted for New York’s higher productivity, significant employment losses, hours reductions, and business closures would be inevitable. Seattle’s much-cited experiment with a $15 minimum wage notably resulted in a meaningful reduction of hours worked for low-wage employees, for example.

What’s more, a growing literature finds that even where firms avoid layoffs, they often adjust in ways that mitigate the net benefits to many low-skilled employees: by reducing non-wage benefits, altering schedules, cutting back on workplace amenities and training, demanding more of their workers, or hiring more experienced employees. There is no free lunch here.

New York City's small businesses, restaurants, corner stores, and hospitality venues—where labor constitutes the dominant cost—would bear severe pressure. New York’s geographical and economic context makes it susceptible to displacement effects too. Companies in industries not tied strictly to local consumption, such as production and logistics, might relocate facilities across nearby borders—like New Jersey or Connecticut—if New York City’s labor costs soar disproportionately. No handwavy theorizing about correcting for “monopsony power” will avoid those adjustments, given this wage floor will be approximately 75 percent of projected median hourly wages or still higher by 2030, even assuming robust wage growth.

Ultimately, the economic effects of Mamdani’s ambitious $30-per-hour wage proposal appear clear: substantial income gains for many workers who remain employed, but significant job losses, reduced work hours, business closures, accelerated automation, and regional employment shifts. This would be a highly risky experiment with the city’s labor market.

Government Grocery Stores

Mamdani has also pushed the idea of city-run grocery stores. This isn’t a price control, but an attempt to undercut market prices for household food items. Mamdani thinks the city can achieve this price goal by a) running government stores that operate on a non-profit basis, b) utilizing city-owned land or buildings that do not require recurring rental payments, c) buying and selling at wholesale prices, centralizing warehousing and distribution efforts, and partnering with local neighborhoods on products and sourcing to reduce transportation costs. Mamdani proposes that the city open five supermarkets, one in each borough, as proof-of-concept.

It is the height of political hubris to presume that running grocery stores is an easy business for government to compete in. First of all, grocery stores make very small gross profit margins, typically 1-4 percent, and operate in fierce localized competition with a range of food outlets. Even on a simplistic static basis, then, the scope for price cuts and across-the-board discounts to customers is tiny. A municipal operator could forgo profit, but the room that creates is only one‑or‑two cents on every dollar of sales.

In fact it’s worse than that because, secondly, grocery chains are only able to offer prices as low as they can, and for quality products in diverse ranges, because they use highly sophisticated international logistics, complex inventory management, supplier negotiations at scale, investments in state-of-the-art refrigeration, and complex pricing strategies to drive efficiency.

Big chains use national bids, just‑in‑time replenishment and advanced demand forecasting—systems honed over decades for razor‑thin margins. These are market-tested because of their impact on the bottom-line. Indeed, as the economist Thomas Sowell has said, “profit is the price paid for efficiency. Clearly, the increase in efficiency must be greater than the profit, or else socialism would in practice have resulted in more affordable prices and greater prosperity.”

Without a profit motive, government-run entities tend not to deliver cutting-edge efficiencies. Attempts to run grocery stores in various areas of the United States are not heartening. Baldwin Market in Florida struggled to buy at competitive wholesale prices and closed in 2024 after persistent losses . A city-owned store in Erie, Kansas found that customers were spending significantly less than necessary for their city-owned store to break even. Failure is not inevitable: Erie, St. Paul has a city effort now said to be turning a small profit, and one could imagine a contracting out or co-op model that would at least survive.

But government-owned enterprises are hardly known for efficiency in general. New York City’s own Housing Authority is burdened with $78 billion in unmet capital needs, inefficiencies, and maintenance backlogs. The optimistic vision of low-cost, low-price, city-run groceries in New York City therefore seems unlikely. It’s therefore a good bet that city-run stores will require extensive subsidies from taxpayers to maintain the low prices Mamdani promises.

Indeed, there is a clear pricing trade-off here. The more that the city attempts to make these stores an anti-poverty tool through price discounts or loss-leader items, the more likely they will follow the example of Venezuela’s Mercal in creating chronic in-store shortages and queuing for low quality products, as well as necessitating high subsidies. Selling at a discount to the market price, of course, will create a big arbitrage opportunity to re-sell goods in a black market. So then the stores might have to introduce rationing of some form, or restrictions on who can access them. Meanwhile, even consumers who benefit from access to the subsidized goods will likely pay an additional non-monetary price in terms of the time and uncertainty costs when shopping.

Even if Mamdani envisages more modest discounts without explicit taxpayer subsidies, it’s important to understand that he is, in fact, proposing subsidies for this endeavor already. The city land or buildings he is promising to use for them have an opportunity cost. Every piece of public land used for these grocery stores means fewer resources and less space available for more productive public purposes like housing, schools, parks, or other essential infrastructure, or else a forgone sale or rental value that could be accessed to give money back to taxpayers.

Of course, having city-run grocery stores also creates political incentives to manipulate pricing, product selection, and even staffing decisions and remuneration for political gain. Local politicians would face relentless pressure to provide favored constituencies special treatment by, say, stocking their products, or hiring certain workers, compounding the risks of cronyism and inefficiency inherent in an entity competing in a market sector but itself operating outside of market discipline.

“Free” Childcare

Mamdani has promised to “implement free childcare for every New Yorker aged 6 weeks to 5 years, ensuring high quality programming for all families.” Again, this isn’t a price control, but an extremely expensive intervention that will formalize childcare into an extension of formal education, in turn severely distorting the industry.

New York state’s formal childcare centers currently average anywhere between $14,000 and $20,000 per child per year, on average, and New York City is obviously at the higher-end of this scale. To provide “free” care for every child in New York City could therefore cost the city alone up $5bn per year, Mamdani thinks. His campaign states that this amount would be supplemented by additional state and federal funding—which is unsurprising, given such a program hinges on state participation, both legally and financially.

Crucially, Mamdani proposes raising childcare workers' pay to match public school teachers. Given that labor comprises 70–80 percent of childcare expenses, this wage increase would dramatically inflate costs of provision that taxpayers would then need to finance. An analysis by Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies suggests that paying childcare workers "living wages" could push the overall annual cost of such a universal program to $9.6 billion. In other words, taxpayers would quickly learn that "free" childcare isn't cheap—and the final bill could be eye-watering.

Naturally, to avoid the city and state government writing a blank check to any private providers through subsidized places, the government would have to restrict payments to a particular level or else impose regulations on what are permissible costs. Experience in the UK suggests that mandating such prices can act like a de facto price control locally by creating shortages of provision in places where costs (such as building rents) might be unusually high.

At the same time, setting a zero out-of-pocket cost for families will increase the quantity of demand for formal childcare services. The city would need to rapidly expand capacity (building new centers or adding classrooms, and certifying many new childcare workers) to meet it. If the expansion lags, you could end up with waitlists – i.e. a rationing by queue instead of by price. It’s possible that initially not everyone would get a slot if the system can’t accommodate all children, leading to frustration.

Progressives nevertheless love this policy. They share a widespread belief that childcare programs produce the triple-dividend of lower out-of-pocket costs for families, increased female labor force participation, and better child development outcomes. The latter is far less convincing for universal programs than those highly targeted at severely disadvantaged kids—and indeed, universal provision can lead to low quality care, while crowding out important private alternatives that help families with different needs. Whether increasing mothers’ labor force participation has broader social benefits that justify any government subsidy is itself debatable. What should be clear is that this is an expensive in-kind subsidy program in an industry that Mamdani wants to make yet more expensive through staff wage regulation.

“Free” Buses

Mamdani proposes making buses completely fare-free across New York City. In practical terms, this means the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) buses in NYC would no longer collect the $2.90 fare from passengers; anyone could hop on for zero cost. According to a February 2023 letter from the NYC Independent Budget Office (IBO), that would cost around $650 million annually in lost revenue. While the Mayor doesn’t directly control the MTA (it’s a state authority), the city can fund bus operations or negotiate with the state. Mamdani presumably would allocate city budget funds to cover the lost revenues, with taxpayers bearing the cost.

Is providing “free” bus transit really a good use of public funds? Mamdani thinks this measure is pro-poor and will improve public safety. Yet buses are extensively subsidized already (with fares only covering 20-25 percent of operating expenses), and further subsidized for the poor in particular via Fair Fares, which offers half-price MetroCards to New Yorkers at or below the poverty line. Nevertheless, many people still don’t use them because they are slow and unpleasant.

Fixing a $0 price will, of course, increase ridership—Mamdani extols a limited NYC pilot program that suggested up to 30 percent more journeys on weekdays and 38 percent on weekends when buses were free. There will also be no need for policing fare evasion with no fare. Yet only 12 percent of users were new riders in the pilot; most of the uplift came from additional journeys from existing users. And if you look at the quality of the service, it unsurprisingly declined. Dwell times increased, bus speeds fell, and customer journey times got longer. A lower price for a fixed supply will make buses more crowded and the process of using them slower.

Mamdani understands this, in principle. He says he wants to make buses faster by building bus priority lanes, expanding bus queue jump signals, and dedicated loading zones to speed up journeys. But that, of course, as well as the need for more buses and drivers, will raise both near-term investment costs and the ongoing costs of provision. So, more expense for taxpayers—raising the question again of whether this is a good priority.

User fees at least provide an incentive for those running buses to improve the quality of service to grow the ridership base. The absence of a price, even a subsidized one, will mean that buses have to compete for taxpayer resources from politicians whose priorities differ from administration to administration. While Mamdani personally wants to subsidize buses more extensively to both improve quality and eliminate fares, we’d expect the quality of service to deteriorate over time under a free-fare policy.

Other Pricing Policies

Mamdani wants to provide “new parents and guardians with a collection of essential goods and resources, free of charge, including items like diapers, baby wipes, nursing pads, post-partum pads, swaddles, and books.”

As a legislator, he supported measures like the NY HEAT Act, which would effectively cap New Yorkers’ energy bills at 6 percent of household income for low to moderate income households.

Mamdani has said that Bill de Blasio was the most successful mayor of his lifetime. De Blasio someone who thought that women were being discriminated against by sexist corporations through 'gendered' product pricing, leading to economically illiterate “anti-pink tax” legislation.

Conclusion

Mamdani is candid: “New York is too expensive.” Yet the toolkit he seeks to deploy—freezing, capping or subsidising prices—brings with it a range of trade-offs. Decades of empirical work tell us that such controls or subsidies:

help incumbent beneficiaries in the short run,

reduce investment and quality,

shift costs onto outsiders or taxpayers, and

often raise underlying market costs.

Under these proposals alone (bus fare elimination, childcare provision, rental housing costs, higher city wages from minimum wage hikes, and grocery story costs), back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that NYC taxpayers might face a bill of between $8 and $11 billion per year. That’s before we account for the broader economic distortions of these price manipulations and any other policies he would pursue.

For readers of The War on Prices, the results are depressingly clear: prices transmit information about relative scarcities and provide incentives to act on the realities of our world. By distorting prices, Mamdani’s policies would bring a range of damaging consequences.

This is not to take away from the points about prices, but I had to quibble:

You wrote that Mamdani has a "permissive approach to crime and disorder". But watching the video you linked, I thought his response was great! We *should* have more social workers and others integrated in communities, people who can be better trained to handle types of situations that cops are not.

Amazing how making New York only 30% white turned it into a socialist shithole.