New Meta-Study Details the Distortive Effects of Rent Control

Attempts to ease rising living costs have resulted in numerous bad policy ideas, not least the return of rent controls.

Currently, Oregon and California have rent control at the state level, while DC, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, and New York allow rent control at the local level. In 2023, California introduced a proposal to tighten its existing rent control law. Concurrently, Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Mexico, North Carolina, Virginia, and Washington have seen recent attempts to enact rent control legislation too.

Rent control, which varies in stringency and scope, refers to government legal limits on rent price levels or rent increases. It is (generally) opposed by economists. As a price control, theory suggests binding caps on rents will produce some combination of shortages of rentable accommodation, lower quality housing, and higher rents for non-controlled properties. Under rent control, landlords will be incentivized to cut maintenance, screen tenants more stringently, convert rentals to owner-occupied units, or condos, or AirBnBs, and, in many cases, halt new rental construction. This all not only directly worsens problems in housing markets, but can induce misallocation, curb labor mobility, and depress property values and local tax bases.

Jeff Miron and Pedro Aldighieri document how the evidence lives up to the theory in a great chapter of The War on Prices. Yet, recently, a new paper by German economist Konstantin Kholodilin confirms their conclusions through a meta-analysis of rent control studies. He analyzed over 100 empirical reports examining 26 potential effects of rent control. The most frequently studied include the impact of controls on covered rent prices, tenant mobility, levels of homeownership, new housing construction, and housing quality.

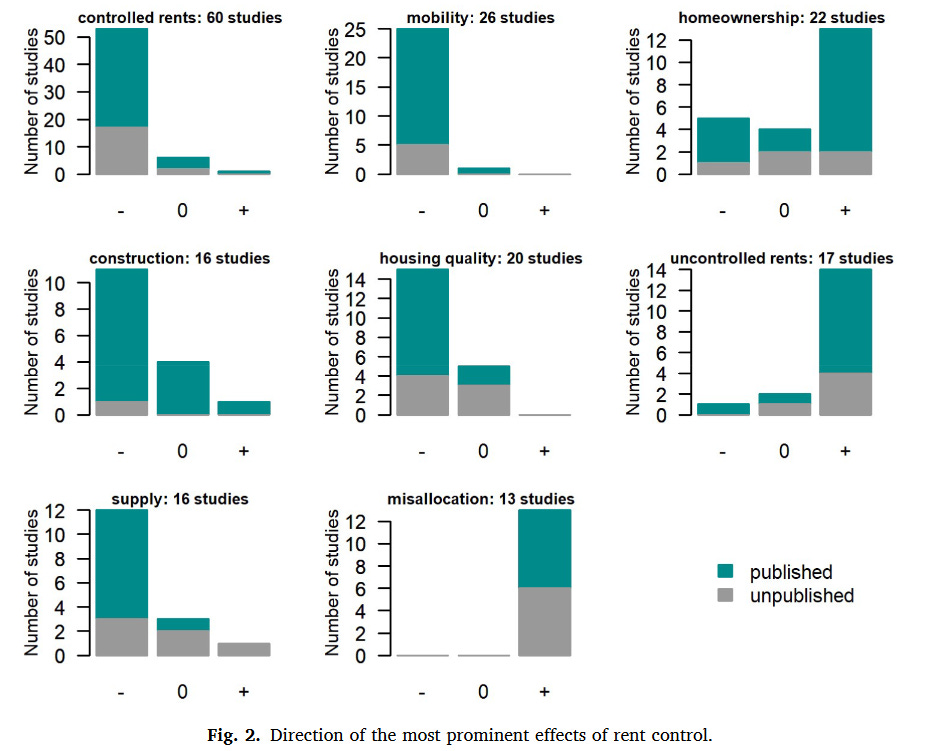

Different forms of rent control have slightly different consequences. Nevertheless, Kholodilin aggregates the studies together to offer big picture conclusions on rent controls’ effects where there have been at least six published studies for a given impact. His results charts are below. The left bars in each portray the number of studies showing rent control has a statistically significant depressive impact on the variable in question, while the right bar shows those finding a positive effect, and the middle bar shows studies that found no statistically significant effect either way.

As you can see, the results align with economists’ intuition. Unsurprisingly, studies overwhelmingly find rent control reduces rent prices for properties it applies to. The broader consequences, however, are devastating.

The research near consistently finds that rent control leads to less mobility (not least, because people don’t want to give up their rent-controlled properties), more people living in properties unsuited to their needs, and higher rents for uncontrolled units. The vast majority of studies examining each find that rent control leads to a lower supply of rental accommodation, less new rental housing construction, and a fall in the quality of rental housing too.

Studies are more divided on the impact of rent control on homeownership rates, although more find rent control increases homeownership than reduces it. This is unsurprising: rent control incentivizes landlords in areas with rising house prices to instead sell for owner occupation. But, of course, this is of cold comfort to the poorest, who typically cannot afford down payments to buy their own homes.

In all, this meta-study once again highlights how rent control is an incredibly crude policy that has a range of negative effects that economists have long predicted and documented.

For more on rent control and rent stabilization policies, read Cato’s new book, The War On Prices.