Greetings, The War on Prices subscribers,

In the U.S. midterm exit polls, 31 percent of voters said inflation was the “most important issue” determining their voting decision - the highest of any listed factor.

But what do Americans actually know - or think they know - about today’s inflation?

The good news is that YouGov explored that question in an extensive U.S. survey in late October. The bad news is that both the questions and results displayed a depressing lack of understanding of basic economics.

Some background

Before seeing why, let’s first ask: what is inflation?

Most textbooks would say it is a broad-based rise in prices across the economy. Individual market prices for goods and services change all the time, due to demand and supply shocks. Rents might rise in Washington DC due to a demand surge from new Amazon HQ workers. Energy bills might rise because of the increased international wholesale price of gas. Childcare prices might go up because of new laws requiring workers to have college degrees to be a childcarer, reducing the supply of care. All these might raise what households consider their “cost of living.” But this, in itself, is not inflation.

Inflation instead is a macroeconomic phenomenon. It occurs when too much money is chasing the production of goods and services in the economy as a whole, resulting in a rise in the aggregate price level. The responsibility for inflation lies with the central bank - here, the Federal Reserve. Since we can’t observe “the aggregate price level,” we proxy for it by creating price indices that measure the change in the cost of a basket of typical goods a consumer might buy. What happens to this Consumer Price Index is then typically talked of as “inflation” in public debates, but it really imperfectly measures the underlying macro issue that we really care about.

In one sense, then, all “inflation” is a result of faulty macroeconomic policy. Taking the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services as given, if central banks and governments conspire through monetary and fiscal policy to allow “too much money” to chase a volume of goods, then the price level will rise, pushing inflation above the central bank’s target.

In reality, most economists would forgive central banks for not being able to accurately forecast the *precise* productive potential of the economy each and every year. And so if there’s an unexpected, economy-wide “supply-shock,” such as the COVID-19 pandemic, or high international wholesale gas prices as a result of the Ukraine war, any unexpected weakening of the production of many goods could also temporarily raise measured inflation for a given level of spending. In other words, it’s perfectly reasonable to state that inflation - at least temporarily - can be driven by very unusual supply-side factors, as well as monetary incontinence.

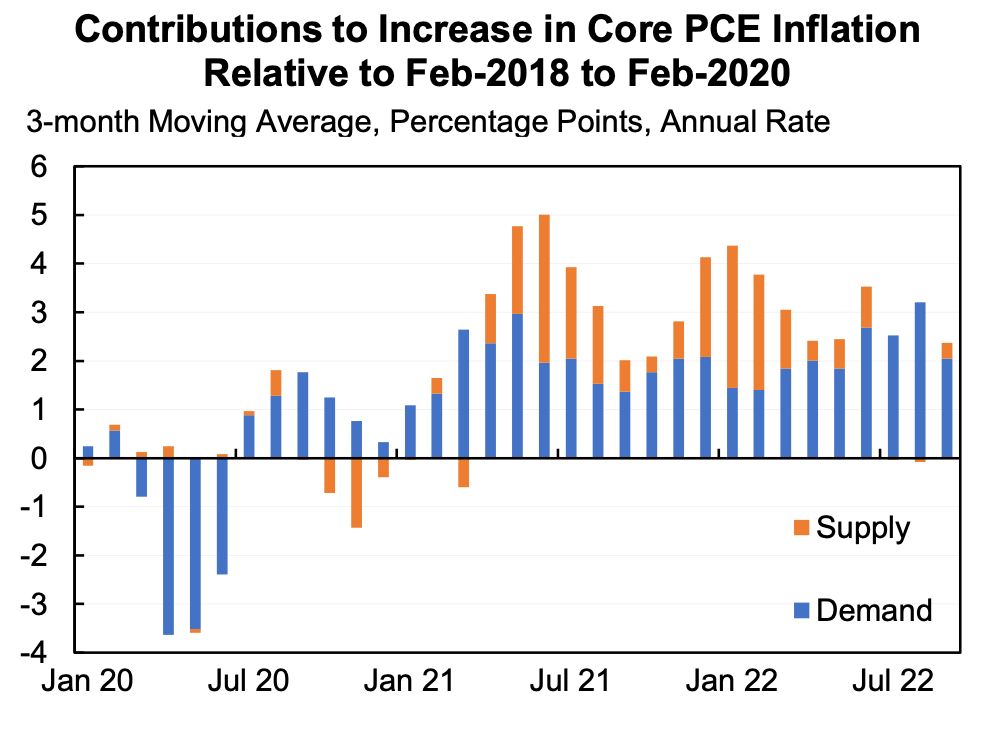

Indeed, one reason why the politics of this inflationary moment has been so difficult is that in the U.S. *both* demand and supply factors have clearly been at play at different times. The economy has seen negative supply-shocks from the pandemic and Ukraine war that have reduced the country’s productive capacity. And yet, even acknowledging this, macroeconomic policy has also been too loose according to pre-pandemic norms, as evidenced by the instability of the growth of overall spending.

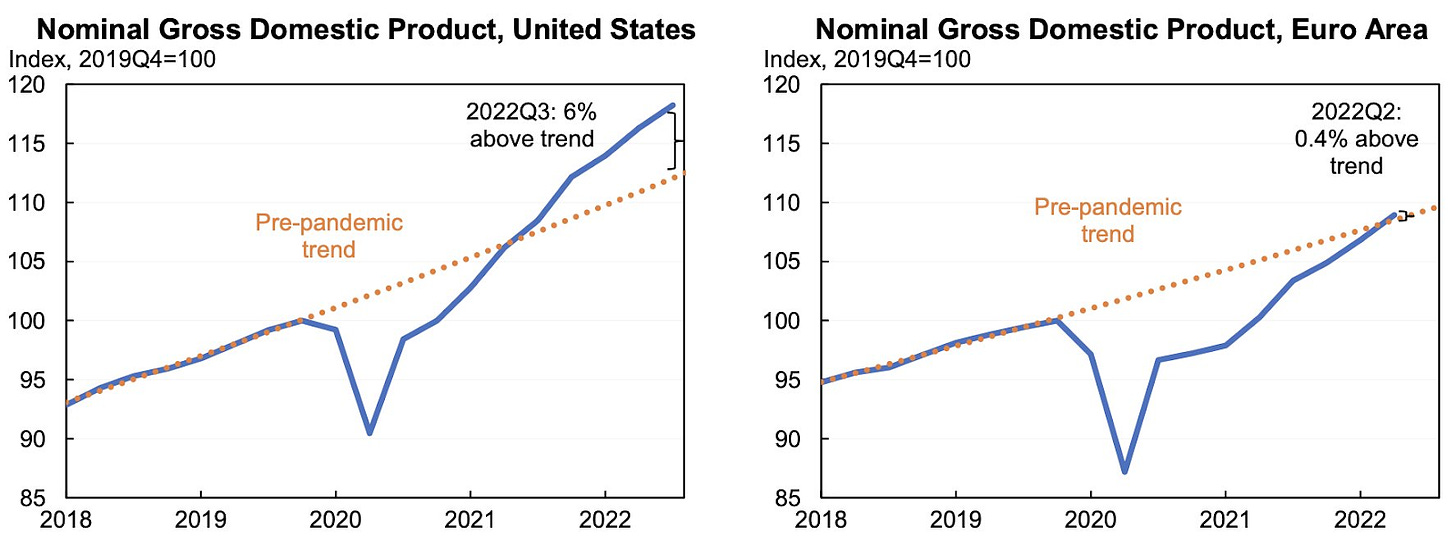

As this chart below from Jason Furman shows, aggregate demand - the overall level of nominal spending in the economy - sped well above its pre-pandemic trend from mid-2021, meaning that macroeconomic policy was generating inflation, even if one generously says the Fed couldn’t have foreseen any impact of the supply-shocks.

Though I’m skeptical that you can really do these types of studies given the complex interactions of prices, economists such as Adam Shapiro that have sought to decompose inflation into supply-driven price increases and demand-driven price increases have frequently estimated that “excess demand” is the key factor driving inflation today.

To YouGov polling…

Given what inflation is and isn’t, it’s deeply unhelpful that YouGov began its survey by asking Americans which goods and services they believed had increased in cost over the past 20 years. For this falls foul of conflating demand and supply changes for individual products over time (relative price changes) with later questions about the macroeconomic concept of inflation. And you soon see that the American public is indeed confused about all this.

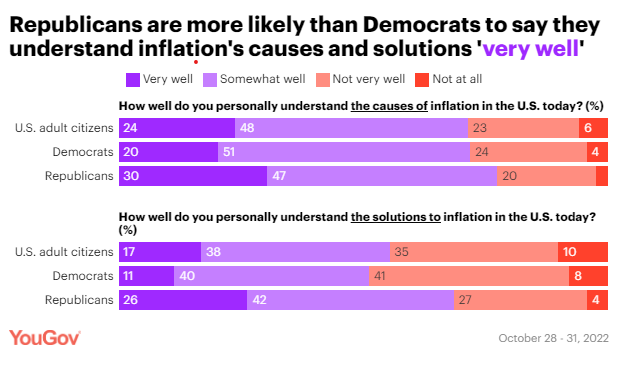

Their answers start reasonably enough: 72 percent of the public say they personally understand the causes of inflation “very well” or “somewhat well.” A far smaller proportion, 55 percent, say they understand the solutions to inflation well or somewhat well. This would be perfectly consistent with someone actually understanding inflation but displaying humility. There’s very few people in the world that understand the intricacies of the Federal Reserve’s operations, after all.

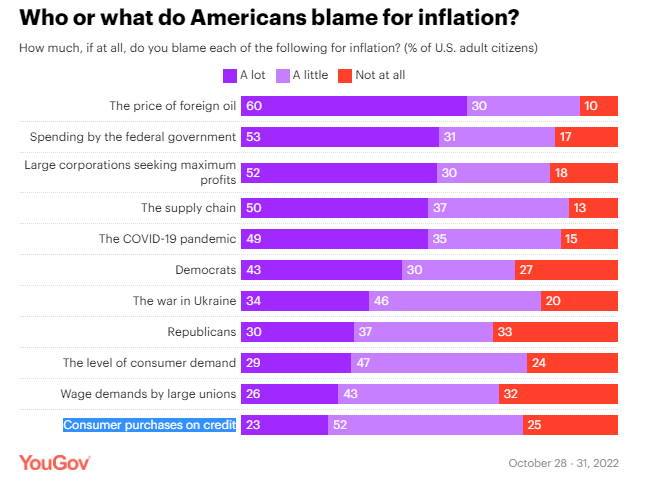

Alas, YouGov’s next question asked “How much, if at all, do you blame each of the following for inflation?” with 11 potential boogeymen listed (see below). The answers do not suggest that people’s understanding of inflation is well-grounded.

The first problem is that “the Federal Reserve” was simply absent as an option for the public to pass judgment on. Whether it be interest rates being too low for too long, too much money in circulation, or any other monetary variable, YouGov simply didn’t give those surveyed the opportunity to blame monetary policy and the Federal Reserve at all for today’s inflation. That is a massive oversight.

Of the options they were given, there were some reasonable responses:

a huge 90 percent of Americans blamed “the price of foreign oil” a lot (60 percent) or a bit (30 percent) for today’s inflation, which, as a contributor through its supply-side impact, is fair enough.

81 percent blamed too much federal spending. Given government institutions printed and borrowed trillions and sent people checks that compensated them far beyond necessary for income-smoothing during the pandemic, this has a strong grounding in several macro theories for increasing the price level too.

84 percent blamed the “COVID-19 pandemic.” This, again, is reasonable given both the hit to supply the pandemic caused and the huge macroeconomic stimulus that was generated in response to it.

Similar magnitude results elsewhere, though, suggest that the blame game is more about folk wisdom than well-thought-through economics.

A massive 82 percent of the public believe, for example, that “large corporations seeking maximum profits” can be blamed for inflation. Yet corporations seek to deliver profits all the time. The only reason profitability might rise alongside inflation is if overall spending is surging relative to output, bidding up prices first while wages are a bit stickier, therefore increasing profit margins. Indeed, if an individual company tried to jack up prices without this, then they would either lose custom, or else their customers would have less money left over to buy other products, reducing demand and so prices elsewhere. Greedy companies can’t therefore cause “inflation” - it is almost always facilitated by aggregate spending being too high.

For similar reasons, the 69 percent of respondents who think that “wage demands by large unions” are to blame for inflation are misguided too. As the price of labor, an inflationary period will be characterized by nominal wages rising sharply and many manufacturers or retailers will observe that they must raise their prices because of these rising (or expected) expenses. But this doesn’t mean rising wages is the underlying cause of inflation. If wages are bid up by an aggressive union without an increase in the supply of money boosting spending, and producers try to pass these costs along by raising their selling prices, most of them will merely sell fewer goods. The result will, again, be reduced output and a loss of jobs. Higher costs can only be passed along in the form of higher selling prices when customers have more money to pay the higher prices. Again, too much money in the economy must be the ultimate underlying cause of an economy-wide inflation.

The blame game turns to policy

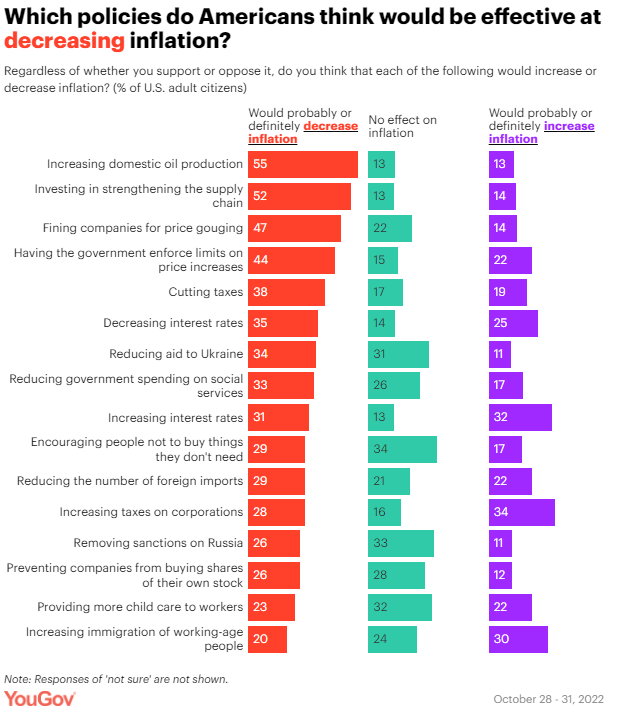

Perhaps unsurprisingly, dodgy views on who is to blame for inflation feeds through into whacky ideas for “solutions” for dealing with it:

47 percent and 44 percent of Americans believe anti-price gouging laws and direct government price controls would be effective at decreasing inflation, respectively.

Yet banning or deterring individual price increases will lead to shortages of those products, bottlenecks and a waterbed effect whereby uncontrolled prices increase for a given level of spending. Economy-wide price controls would be a disaster too - with historic experience showing businesses allowing product quality to deteriorate or shrinkflation to occur to reflect the controlled prices, or else a sharp rebound in prices to their true level when controls are lifted.

Many more Americans believe cutting taxes and reducing interest rates will reduce inflation than increase it.

I doubt this is because they hold complex views that targeted tax cuts could boost aggregate supply substantially or because they are neo-Fisherians on monetary policy either. What this suggests to me is that people associate “inflation” with the cost of living generally, rather than see it as a consequence of expansionary macroeconomic policy. Since paying taxes and mortgage costs are also living costs for many people, they think lowering taxes or reducing interest rates would ease the squeeze on them and so see these policies as disinflationary.

More Americans believe “reducing the number of foreign imports would decrease inflation” than increase it.

While protectionism would only have the direct effect of raising the relative price of those goods protected (not inflation), doing more of it would make the economy overall less productive. If anything this would slightly raise the prospects for temporary inflation for a given level of spending.

A net 10 percent of Americans believe that “increasing immigration of working-age people” would increase inflation.

Again, the impact of immigration would primarily alter relative prices. The net impacts of more immigration are complex because more workers would boost the supply of goods, but their spending boosts demand too. I suspect Americans take the position that more migration would raise inflation because they envisage things like higher house prices - again, conflating “inflation” with the cost of living of essential goods.

Where do these views come from?

The best explanation for why the median American holds quirky views on inflation is that they see inflation itself as synonymous with certain day-to-day living expenses. So, anything that they think might reduce their major out-of-pocket expenses - lower taxes, lower mortgage rates, less greedy companies, less greedy unions - is deemed good for reducing inflation too.

The question then becomes: where does this misguided understanding of inflation come from?

Part of the problem, no doubt, is just a lack of basic economic literacy - not just among the public, but in the broader debates around inflation that the public hear. One reason that I started writing The War on Prices is because I could see that this inflationary moment was leading to all sorts of bad ideas resurfacing, whether theoretical (wage-price spirals) or policy-based responses (price controls). The fact that YouGov didn’t even include the Federal Reserve as a source of blame for inflation speaks volumes. The conflation of inflation with individual price changes is also pervasive.

And, to be honest, the blurring of some of these theoretical distinctions between relative price changes and inflation are not always a bad thing from a policy perspective. Though high inflation periods can lead to mischief with price controls and demagoguery against companies, it can also be a spur to genuinely beneficial deregulation of important industries (see the Jimmy Carter- Ronald Reagan period). If the U.S. removes supply-side constraints against new energy production today, this could have similarly beneficial effects now.

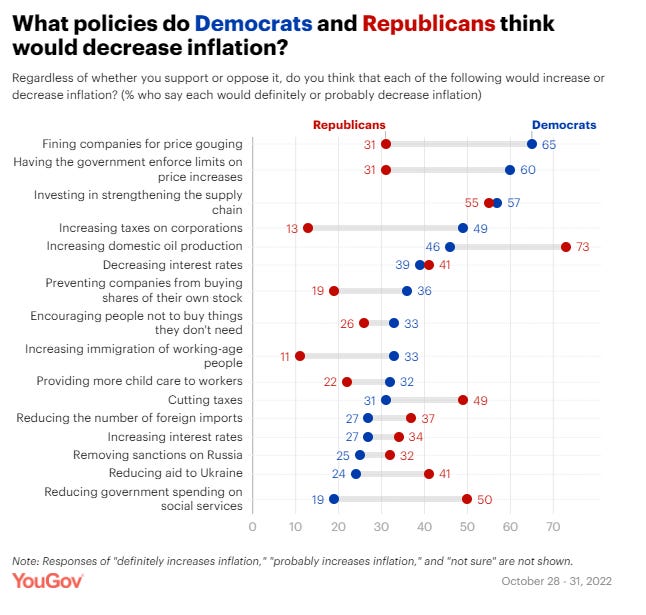

It’s difficult to look at the results by party identification, however, and not conclude that there is also either a top-down absorption of political narratives by party, or perhaps even that respondents tells pollsters what they think a Republican or Democratic loyalist would say.

Democrats are most likely to blame corporations, foreign oil prices, the pandemic, supply-chains, and Republicans for inflation. Republicans are most likely to blame federal spending, Democrats, and foreign oil prices. Both these sets of explanations are obviously convenient electorally for passing the buck when one considers the periods of time in which the parties occupied the U.S. Presidency.

And the blame game feeds through into policy solutions too. Democrats think that price controls, investing in supply chains, and taxing corporations are the most hopeful ideas for reducing inflation. Republicans say it is increasing domestic oil production, cutting taxes, and reducing government spending. Though not all elected politicians from either party would agree with these prescriptions, they do broadly reflect the stated policy positions or complaints from prominent members of the Dems and GOP.

Americans and pollsters, then, have rather misguided opinions on what inflation is and what caused it this time. At least part of this seems to just be a folksy conflation between inflation and certain important product prices. Add to that the way that everything in the U.S. has become politicized and it’s clear that, except for the role of Vladimir Putin, there’s little shared economic narrative among American voters about inflation or how to deal with it.

OTHER THINGS

My Times column this week argued that if the Tories were serious about a fiscal framework to restrain debt, they should look to Switzerland, where it has actually worked.

Several states and DC are chasing the price level with aggressive minimum wage hikes (ugh).

That’s all for now!

Ryan

"Quirky". You are too polite. :)