Trump's Latest: Credit Card Interest Rate Caps

Former President Donald Trump has tried to position himself as the voice for financial freedom on the campaign trail, but his latest proposal to restrict credit card interest rates seems to be something out of left field.

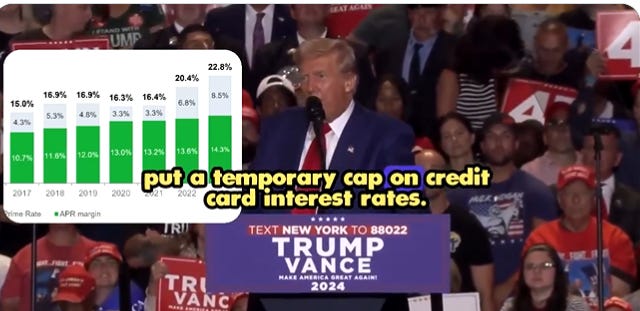

Last night in New York, Trump said, “While working Americans catch up we're going to put a temporary cap on credit card interest rates we're going to cap it at around 10 percent. We can't let them make 25 and 30 percent.”

The proposal comes as a bit of a surprise. On one hand, it’s possible the proposal came from his running mate: Senator J.D. Vance (R-OH). Senator Vance made waves in 2023 when he pushed legislation to restrict credit card companies. However, one of Senator Vance’s first moves when he joined the campaign was to back off this idea.

Perhaps instead he borrowed the idea from Vice President Kamala Harris. But this would have been an odd choice because Harris came under considerable criticism for proposing price controls as part of her economic agenda. The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell warned:

It’s hard to exaggerate how bad this policy is. It is, in all but name, a sweeping set of government-enforced price controls across every industry, not only food. Supply and demand would no longer determine prices or profit levels. Far-off Washington bureaucrats would. … At best, this would lead to shortages, black markets and hoarding, among other distortions seen previous times countries tried to limit price growth by fiat.

In fact, even Trump criticized Harris for this proposal. During last night’s speech, Trump himself said, “[Vice President Harris’s] only idea for solving inflation is to impose communist inspired price controls which have never worked.”

So, between his own vice president abandoning such restrictive policies, his opponent coming under fire for similar plans, and he himself condemning “communist inspired price controls”, Trump’s endorsement of price controls for interest rates on credit cards comes as quite the surprise. But if one thing is clear, it’s that politicians on both sides of the aisle are in dire need of a better understanding of economics.

When policymakers decide that the market rate is too high and impose an interest rate cap, they leave businesses with two options: reduce the quantity or the quality. In other words, consumers will either face a shortage or receive lesser products. Either way, consumers lose.

Although the details are limited, the most likely effect of Trump’s proposal to restrict credit card interest rates at 10 percent is that anyone deemed “too risky” would have their credit card shut down. Without access to this line of credit, they may turn to family, friends, or payday loans to bridge the gaps in their spending. Alternatively, they may pay bills late or skip payments altogether. How this plan would help “working Americans catch up” is a mystery.

The experience with payday loan restrictions already demonstrates how bad this policy would be. For example, one study looked at the effect of the 36 percent interest rate cap in Illinois and found that both the availability of small-dollar loans and the status of consumers’ financial well-being had decreased in the two years after the enactment of the restriction. Most notably, the number of loans that were issued to the financially vulnerable fell by 44 percent in the six months after the rate cap was enacted.

As I wrote in Ryan Bourne’s latest book, The War on Prices, interest rate caps may be intended to make credit more affordable, but economic theory and experience both show that price ceilings harm many consumers in practice. If policymakers truly want to help expand the reach of financial services at lower cost, they should turn toward freeing, not restricting, the financial system.

Are you interested in learning more about how price controls distort the market? Ryan Bourne’s latest book, The War on Prices, is available here and features 24 chapters that will walk you through price controls large and small.

The Trump campaign did not respond to my request for comment by the time of publication.