Superabundance: Is Global Population Growth Using Up The Earth's Resources?

Time prices and their limits

Greetings, The War on Prices readers!

Last week, I finally got the chance to dig into my colleague Marian Tupy and Gale Pooley’s wonderful new book, Superabundance: The Story of Population Growth, Innovation, and Human Flourishing on an Infinitely Bountiful Planet.

I can’t recommend the weighty tome enough. It deserves a full review when time allows, but for now just know that you should order your copy and absorb its wisdom. Marian has a great preview in this week’s issue of The Spectator to whet your appetites.

The pair’s central thesis - proven in devastating detail - is that, contrary to the doom and gloom you hear about a growing global population pillaging the earth of its resources, relatively simple economic indicators show the opposite. In fact, virtually all major commodities (bar crude oil and gold, even then only over certain time periods!) have actually been *increasing* in abundance, rather than becoming more scarce.

How on earth can we explain this fact?

Well, modern day Malthusians such as Prince Charles and David Attenborough might tell us that human beings are a drain on the planet’s scarce resources. And, yes, a larger population does, of course, create some acute environmental externality issues that must be dealt with (whether plastic in the oceans or carbon emissions).

But when it comes to the availability (or abundance) of commodities, the idea that higher population levels lead inexorably to us “running out” of stuff ignores a) the incentives inherent within a market economy to react to price signals; combining with b) the fact that a larger population expands our most important resource: human brains - the origin of ideas that dream up innovative new ways of doing things.

In the spirit of the late, great Julian Simon, Tupy and Pooley admit that, yes, population growth might, in the first instance, raise demand for a commodity, pushing up its market price. But that same larger population also provides the intellectual fuel to act on this price signal - finding alternative sources, new means of extraction, productivity improvements, or economizing on its use - such that, overall, the commodities actually become more abundant, not less.

How can we tell they have become more abundant? Well, economists don’t go around counting how much of a resource is left. We use changes in prices to examine whether something has become scarcer or more abundant over time. And Tupy and Pooley show that for a vast range of commodities, prices have fallen drastically as the global population has grown.

Tupy:

“The personal abundance of the average inhabitant of the globe rose from 1 to 6.27, an increase of 527 percent [between 1960 and 2018]. Put differently, for the same amount of time that one needed to work to buy one unit in a bucket of resources in 1960, one could get more than six in 2018. Over that 58-year period, the world’s population increased from 3 billion to 7.6 billion….

…personal resource abundance increased faster than population in all 18 datasets that we analyzed. We call that relationship “superabundance.” Simply put, on average, every additional human being created more value than he consumed.”

Introducing the time price

You might have noticed that the methodology used for assessing these changes harnesses a concept called a “time price.” Rather than trying to inflation-adjust prices over time to calculate how the “real” price of a good has changed, the pair calculate the time that a buyer must work in order to earn enough money to buy a unit of something.

As the book explains:

“If an item costs you $1 and you earn $10 per hour, then that item will cost you 6 minutes of work. If the price of the same item increases to $1.10 and your hourly income increases to $12, then that item will only cost you 5 minutes and 24 seconds of work.”

Time prices are thus expressed in time units (minutes, hours, days etc), and not dollars. And this approach has some clear advantages over inflation-adjusting prices when we are concerned with examining affordability and abundance/scarcity, comparing across countries, and looking over long periods. As Jeremy Horpedahl explains:

It’s the superior method when you are looking at the price of a particular good or service over time, compared with a naïve inflation adjustment, which only tells you if the price of that good/service rose faster or slower than goods or services in general, not if it’s become more affordable. Inflation adjustments are really only useful when you are trying to compare income or wages to all prices, to see if and how much incomes have increased over time.

Time prices, then, are the best way to judge whether population growth is “using up” stuff. That’s because time prices capture more fully the gains of innovation - which can show up in both lower prices and higher incomes.

There are practical advantages to looking at time prices too. All that is required to calculate them is data on nominal prices and nominal incomes or wages per hour, with no complex adjustments necessary to take into account how a consumer spending basket has changed. You can use the same method for any country’s currency and for any point in time, meaning that you do not have to worry about exchange rates or Purchasing Power Parity adjustments to compare, say, the affordability of something in the UK and U.S. too.

What do time prices show?

And the key findings when looking at commodity time prices are really, really dramatic. The pair use a whole range of different datasets to test the robustness of their conclusions. All point to the same trends. But as a typical example, let’s take their analysis for 1960-2018 of “The World Bank 37 commodities” - aluminum, bananas, barley, beef, chicken, cocoa, coconut oil, coffee, copper, corn, cotton, crude oil, fertilizer, gold, groundnuts and groundnut oil, iron ore, lead, logs, natural gas, nickel, oranges, palm oil, platinum, rice, rubber, sawnwood, shrimp, silver, sorghum, soybeans, sugar, tea, tin, tobacco, wheat, and zinc.

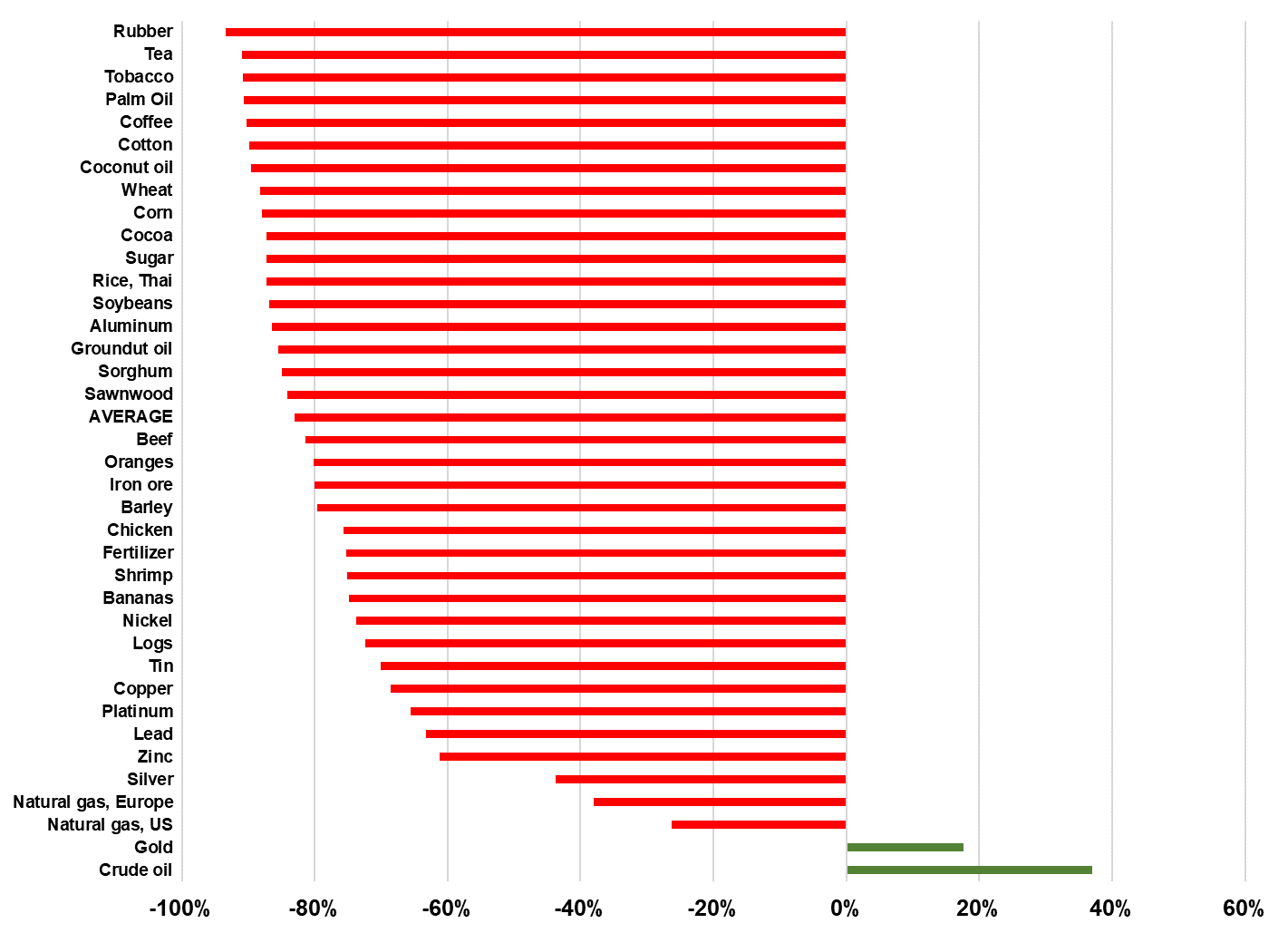

The average time price of these commodities globally (that is, the nominal price in global markets, divided by global nominal GDP per hour worked) fell by a massive 83 percent between 1960 and 2018, with just two commodity time prices rising (gold and crude oil). The time price of rubber fell 93.4 percent, for example, while wheat fell 88.2 percent, and lead 63.2 percent. As you can see from Figure 1, the overall time price reductions for the commodities examined have been astounding.

Figure 1: Changes in the Time Price of the World Bank 37 Commodities (1960-2018)

The same data can also be used to examine the average commodity time price change by country. The largest fall was in Ireland, which saw a 96 percent decline; the smallest, Mexico, saw a 70 percent decline. The United Kingdom and the United States saw 86 percent and 72 percent time price declines for the average of these 37 commodities respectively over this period, equivalent to our personal resource abundance doubling every 20 years (UK) or 30 years (U.S.)

The analysis appears to extend beyond raw commodities to U.S. consumer goods and food, and even cosmetic surgery. The same trends hold across all countries examined.

The sheer scale of this data, then, doesn’t just kill the idea that population growth makes resources scarce. It buries it a mile underground, fills in the hole with concrete, and puts Fort Knox style security around the site. The data is simply devastating to the view that humans are draining our planet’s resources or exhausting Mother Nature’s inheritance. The time price of these commodities and goods examined has collapsed, showing how human ingenuity and market incentives can combine to ensure their widespread abundance, even when the number of mouths and bodies has rocketed.

The limits of the time price?

Time prices are thus very instructive when looking at the change in the scarcity or abundance of basic commodities. But is this methodology something we could apply more broadly? And what, exactly, do these time price results tell us?

Before we charge off to overhaul the way we think about tracking economic welfare more broadly, it’s worth being aware of where time prices face the same problems as conventional price indices and why we should be careful about talking of the magnitude of their falling as synonymous with the magnitude of economic welfare improving.

First, beyond looking at things like raw commodities, the time price change methodology still faces the problem of needing quality-adjustments. Suppose we examined TVs. It may well be that the time price of the average TV on the market has fallen significantly over decades. But this might vastly understate the real gains in economic welfare experienced, since a modern, smart TV obviously has a much higher picture quality and additional functionality than an old cathode ray tube job.

In other words, we still face the challenge of the need to compare like-with-like. That’s relatively easy with commodities such as copper; less so with “going to the movies” or banking. As the authors state: their interest was primarily about population growth and the earth’s resources, but future research might extend this approach to other sectors, including in services, where the picture of affordability may well be messier.

Second, there are theoretically rare instances when interpreting the time price as a pure improvement in wellbeing might overstate living standard gains, because we wrongly attribute falling demand for a product to an improvement in welfare. Suppose, for example, that it was found that a certain commodity caused cancer. Demand may plummet, pushing down the good’s price, despite population growth. That the number of hours of work required to buy that product falls is not then indicative of progress. Rather, it reflects the fact that fewer people want the good.

For the goods selected by the Superabundance authors, this theoretical possibility shouldn’t worry us. Looking down the list, all commodities are things that would be regarded as desirable or, at least, wanted or needed. But this is a manifestation of the old problem of making sure that the goods in a basket you are tracking are representative of what consumers actually demand in order to accurately jump from affordability changes to living standards changes.

Beyond this, there are two other things we must be careful with when assuming improved affordability represents a pure improvement to human wellbeing.

One is that rising wages obviously are a big driver of falling time prices, but we cannot just assume higher wages are a consequence of innovation and progress. They may also reflect more intensive human capital accumulation, where workers give up time working initially to “invest” in acquiring skills to earn higher pay. To then look at the falling time price as a pure welfare gain may ignore this initial sacrifice, and so somewhat overstate the net gain to living standards.

Finally, it’s possible that a time price fall might also overstate the gain in economic welfare by assuming that the value of leisure between two periods is unchanged. Suppose a good costs $1 in 1960 when someone earns $10 per hour, so the time price is 6 minutes. If the quality-adjusted value of leisure to the individual doubled by the year 2000, then the time price would need to fall to 3 minutes for their overall welfare to remain unchanged, because the opportunity cost of leisure is higher.

To fully assess the change in economic welfare, in other words, we have to “quality-adjust” for leisure time too. Again, I don’t think this effect is big enough to change the interpretation of the results from a welfare perspective, but it’s worth pondering to avoid overstating the case…

A novel way to think about inequality too…

These theoretical wrinkles aside, the results presented are so clear that the authors do not (and do not need to) exaggerate their implications: the time price measures are clearly an intuitive way of assessing abundance and they consistently show resources becoming more affordable and abundant, even with the population growth we have seen.

And for those concerned with such matters, looking at those time price changes can really make you think differently about what is meant by economic inequality too.

Tupy and Pooley give an example of Raj in India and Ray in Indiana

In 1960, Raj spent seven hours a day earning the money he needed to buy rice for his meals. By 2018, TP [the time price] of rice had fallen 86.2 percent. Now Raj’s grandson only works 58 minutes to buy his rice.

Meanwhile:

In 1960, Ray spent one hour a day earning enough money to buy wheat for his meals. By 2018, TP of wheat had fallen 87 percent. Now Ray’s grandson works only seven and a half minutes to buy his wheat.

Both are better off, but has inequality increased? In one sense, yes:

In 1960, Raj worked 7 times as long as Ray to buy his food. By 2018, Raj’s grandson worked 7.73 times as long as Ray’s grandson.

But…looking at the change in absolute time worked:

Between 1960 and 2018, Ray’s grandson gained 52.5 minutes of time, but Raj’s grandson gained 362 minutes of time. Put differently, Raj’s grandson gained 6.9 times more time…

As should be evident from this worked example, the sort of resource abundance we have seen bestows huge benefits to the very poorest in society.

Buy the book!

All that sounds interesting, right? Well, this newsletter has barely scratched the surface on the content of this work. There’s a ton of interesting data in the book, as well as extensive and fun examinations of historical worries about the world going to hell in a handcart, the Julian Simon vs. Paul Ehrlich resource bet, and the threats to continued progress posed by modern ideologies, such as extreme environmentalism. The authors are fine writers.

This volume fits very neatly alongside Hans Rosling’s Factfulness, Matt Ridley’s The Rational Optimist, Deirdre McCloskey’s Bourgeois trilogy, and Steven Pinker’s books as one of the most important works documenting how the world has improved dramatically since the great take-off in living standards.

It is particularly timely, as it is published a) when many are worried again about the impacts of a large global population on the planet, and b) when we are live through extensive commodity price disruption because of the war in Ukraine.

The evidence presented shows we should be optimistic about the long-run. We are not “running out of resources” and must not let that misconception frighten us into turning our backs on markets or demanding fewer people exist.

Please: buy the book!

WAR ON PRICES UPDATE

In the latest salvo in The War on Prices™ (US edition) California legislators have passed a bill to introduce a sectoral wage board for fast-food chain workers. Under the legislation, a corporatist “10-person council, comprised of business, labor and government representatives” would “establish an industry-wide minimum wage, as well as health and safety standards” for chains with 100 or more establishments nationwide. The minimum wage the council sets would be capped at a maximum of $22 per hour, with restrictions on how much it could increase each year after that. For reference, in 2021, the average hourly wage for fast-food workers in California was $15.61.

In the latest salvo in The War on Prices™ (UK edition) the Westminster government is consulting on plans to tighten rent controls in the social housing sector to significantly below the general housing inflation rate. Sigh.

David Henderson references a beautiful passage from Alchian and Allen’s textbook on how, despite overly stimulatory macroeconomic policy as the ultimate cause of inflation, it can very much feel to most participants in businesses as if the cause is a rising cost base. Worth reading and digesting.

OTHER THINGS

My Washington Post piece writes up my thoughts on the disaster of DC’s requirement that childcare workers have a college degree.

My Times column this week was on political myopia. A video of Nick Clegg has been doing the rounds from 2010 in which he dismisses new nuclear power because it wouldn’t be onboard until “2021, 2022.” Now, nuclear power is generally uneconomic without extensive subsidies or a massive carbon tax. So I didn’t dunk on Clegg for his lack of foresight about Ukraine. But the way he talked of 2022 as some way-off distant time period exemplifies the high discount rate of politicians - how much they favor the present over the future.

Someone has unearthed an amazing Virginia Postrel article from **1996** which, if you substitute the word “Buchananism” for “national conservatism” is the most comprehensive description of the elite national conservative worldview. There’s nothing new under the sun.

Have a great weekend!

Ryan