Last month, one of us wrote about how progressives in Congress were using tariff-induced price hikes to revive kooky ideas about “greedflation.”

Their claim is that when you get a supply shock—a pandemic, war, big tariff hikes—companies “take advantage” of the chaos to jack up prices well beyond their cost increases, pushing up headline inflation. Why firms suddenly gain the market power to do this, or why consumers can suddenly acquiesce, is rarely explained. But a lot of people seem to believe it.

Cue July’s Producer Price Index. The headline index of domestic producers’ prices jumped by 0.9 percent month-on-month and 3.3 percent year-on-year. This was a hotter-than-expected inflation read, that some instantly blamed on tariff-induced price hikes.

But the greedflationists are telling another story. Matt Stoller points to this particular Bureau of Labor Statistics line: “Over half of the broad-based July increase is attributable to margins for final demand trade services, which jumped 2.0%.” He takes this to mean that, far from tariffs lifting producers’ prices, higher inflation is being driven by distribution firms widening their price margins, using tariffs as an “excuse” to raise prices further than justified by their costs of acquiring goods.

We think that’s a misunderstanding of both the series and the economics of tariff increases.

What “trade services” is

Let’s start with definitions. In this PPI “trade services” series, retailers and wholesalers are treated as providing a service: distributing goods. This service includes merchandising, storing, displaying, and making goods available to either retailers or customers.

The price of this service cannot be measured directly, so it’s calculated as the gross resale margin (i.e. the selling price for the wholesaler minus the cost at which they acquire the item from producers, or the selling price for the retailer minus the cost at which they acquire the item from wholesalers).

This, then, is a markup accounting concept and a gross margin, not a full-blown profit series. It excludes the mundane things that can make or break profits, like payroll, rent, card fees, logistics etc. But even aside from this index not being a profits series, it’s wrong to presume that increases in it are synonymous with an increase in greed or market power.

How a tariff shock can push this index up

Stoller’s story assumes tariffs raise the cost of acquiring goods and so, at most, the wholesalers and retailers in this index should pass on those specific cost increases in their selling prices. By this logic, margins might compress with tariffs, but at worst they should stay constant. That they have gone up and so contributed positively to the rise in the PPI is taken as evidence of firms taking advantage of the tariff environment to raise their margins.

But the real-world effect of tariffs on these short-run margins is ambiguous (as this BLS video explains). Yes, tariffs can directly raise acquisition costs for firms. But several tariff-induced mechanisms can push trade services margins up by altering sale prices without requiring any morality play about “greed.”

Tariffs induce substitution. New tariffs raise the price of foreign goods, leading to demand substitution to other products or domestic substitutes, which can’t be ramped up overnight. When customers have fewer places to turn and supply is tight, the uplift in demand means stores can lift shelf prices relative to their wholesale costs. In other words, margins widen for specific products until supply can adjust. Indeed, in serious macroeconomic models, supply disturbances (tariffs included) show up as markup shocks.

In fact, tariffs can nudge buyers and merchandisers toward domestic substitutes or private-label lines that carry bigger margins to begin with. So even if product-level markups are unchanged, the average margin the PPI captures can rise when tariffs cause such substitution, simply because a larger share of people have diverted their demand towards higher-margin retailers.

Inventory timing. Firms often anticipate tariff hikes and scramble to obtain orders before input prices rise. After the hike, they may sell older (cheaper) inventory into a market with higher going market prices, which can boost accounting gross margins temporarily. Technically, in the PPI, the trade-services margin should be calculated off the current acquisition (replacement) price, not yesterday’s costs. So inventory timing by itself doesn’t automatically lift the PPI margin. But it can rise if shelf prices reset faster than suppliers’ current quotes or if effective acquisition costs (after rebates/allowances) lag—both of which can create a temporary pop. As cheaper stock runs out and new, higher-cost deliveries arrive, of course, any temporary margin boost fades. We saw exactly that pattern this year: a big jump in real imports in Q1 (+8.4%) and a fall in the early Q2 (-8.6%) data. This sequencing alone can fatten realized profits.

Notice what neither of these require: a sudden epidemic of “greed.” They are mechanical consequences of a tariff policy that itself reshapes the competitive landscape and distorts demand patterns. If you don’t want these effects to occur, then it’s probably best not to impose new large tariffs to begin with.

It’s also a volatile series (and that matters)

Because each trade services margin depends on two moving prices (the selling price and the acquisition cost), economic forces changing either of them can generate large monthly swings in the series. The BLS admits as much.

We crunched the numbers on month-to-month volatility (see table below). Since COVID, trade services “prices” have been more volatile than food. Food prices, of course, are deemed sufficiently volatile that economists usually strip them from “core” inflation measures.

This volatility of trade services is important, because it creates a cherry-picking temptation. July’s +2.0 percent margin pop is waved around as proof of rampant profiteering, but last July the PPI was flat with an almost 2 percent fall in trade services “prices.”

Did we see pieces at the time from progressives celebrating this as altruistic deflation from businesses? Of course not. But that’s the point: economically, it makes no sense to think greed switches on and off. The simpler explanation is that these gross margins can move with macroeconomic forces and major policy change.

In short: this sub-index isn’t a profits measure, can rise because of tariffs, and is itself highly volatile. Using it as a proxy for corporate “greed” to explain rising inflation is flawed. Sadly, that’s par for the course in most greedflationist analysis, where even BEA profit data only gets airtime when it flatters the thesis.

The better read of July

July’s PPI index was hot across the board. Even “core” measures like PPI less food, energy, and trade services increased 0.6 percent in July alone.

Tariff defenders, such as vice-president JD Vance, were quick to use June’s PPI report, which showed unchanged prices, to claim that economists were wrong about tariffs. They have been suspiciously quiet following this most recent PPI release. The truth is that supply shocks, like most economic forces, take time to show up in macroeconomic data.

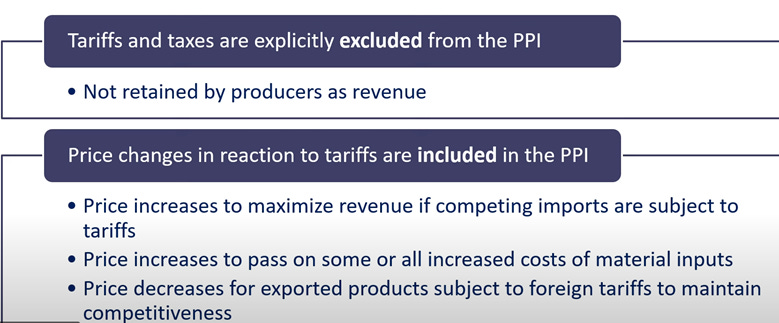

The most likely first mover in response to tariffs is import prices. Import prices were relatively unchanged in June but that’s a bad sign for American consumers—tariffs are excluded from import prices and instead included in government expenditures since the BLS (rightly) designates tariffs as a tax. The fact that import prices were steady rather than falling suggested that US importers had to pay all the tariff costs.

It is possible that July’s sharply increased PPI report was the next domino to fall in the chain of price passthroughs that ultimately ends with US consumers. July’s CPI report already shows that core CPI grew 3.1 percent year-over-year, and this may get worse in the coming months.

It is important to remember that while most of the attention has fallen on the price effects of tariffs, actual consumption will also be affected as shoppers will have a smaller selection of goods to choose from. Tariffs also encourage more resources to flow to protected industries that would otherwise be uneconomic. Increased prices and lowered consumption will therefore occur alongside lower output and less productive employment.

The obsessive focus on the effects of tariffs on inflation is understandable given we’ve just lived through a big inflation spike. But the main impact of tariffs is that they make us poorer. Yes, they are stagflationary in the immediate term—both reducing real output and raising the price level. But in the longer-term they simply make us less well off than in a world without them.

Greedflationists and members of Congress would do better to focus on these real economic consequences of the policies, rather than scapegoating businesses—yet again—for problems made right here in Washington.