Does Economic Inequality Really Worsen Pandemics?

A critique of a new UN report endorsed by Joe Stiglitz

During the 2010s, there was a raft of…shall we say, speculative research on the ills wrought by high levels of economic inequality.

Concern about income disparities was the defining zeitgeist. Former President Barack Obama described inequality as the “defining challenge of our time” and Pope Francis tweeted that “inequality is the root of social evil.”

Wide outcomes between rich and poor were not just deemed consequences of unjust economic trends, which is why Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton said we might worry about inequality. No, a raft of books and papers argued that income inequality itself could be a cause of other downstream social or economic ills.

The Spirit Level, for example, suggested high inequality led to bad health outcomes. Some weird IMF papers said high inequality slows economic growth. Raghuram Rajan speculated that rising U.S. income inequality created political pressure to prop up living standards via easy credit—especially subsidized housing finance—fueling the subprime housing boom that underpinned the financial crisis. Thomas Piketty’s Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century warned that economic inequality was bound to continue growing and produce social unrest amid democratic capture by the wealthy.

And then, suddenly, this type of analysis—usually based on some loose correlations or else highly speculative theories—became passé. Intellectually, there was robust pushback on the shoddy analysis contained within these books and reports. Many were plagued by p-hacking and the impact of outliers on the results. But more than this, in the aftermath of President Trump’s 2016 election victory and Brexit, it was clear that worries about economic inequality (which were always an elite, rather than a broadly shared public concern) were not of frontline political importance.

Nevertheless, a cottage industry has persisted in producing reports that blame economic inequality for all the world’s ills. You see the same people in left-wing think tanks and international organizations like the UN pushing this narrative year after year. The policy implication is usually that we need progressive solutions like “predistribution” through powerful trade unions and regulation, larger welfare states, and higher taxes on the rich to narrow income gaps. And one economist who has become part of this group of advocates is Nobel prize winner Joseph Stiglitz.

So when I saw on X that there was a new UN Global Council on Inequality, AIDS and Pandemics report looking at the link between pandemics and inequality, a council on which Stiglitz sits, I could hazard a guess about what it would say: that high income disparities made countries more vulnerable to the spread of infectious disease. Sure enough, the report was summarized as showing that: “Inequality is making pandemics more likely, more deadly and more costly.”

This grabbed my attention, because it combined two themes I’ve written about extensively: motivated reasoning about the supposed costs of economic inequality and attempts to use the COVID-19 pandemic as proof that people’s favored policies were desirable all along.

Pandemic Outcomes and Income Inequality

I have neither the time, nor knowledge, to assess the whole UN report, which covers HIV infections and AIDs mortality too. But I did head straight to the section (and underlying paper by John Ele-Ojo Ataguba , Charles Birungi, Santiago Cunial and Matthew Kavanagh for the BMJ Global Health) that purports to show that higher economic inequality in countries led to worse mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The core empirical result comes from a simple cross-country regression. The authors line up each country’s COVID-19 period “excess deaths” around the world (how many more people died in 2020–21 than you’d expect normally, or for some countries what the epidemiological model estimated would happen). Then they regressed it on a measure of income inequality (the pre-tax and benefits Gini index), while controlling for three other factors: a country’s income category, health spending per person during 2020/21, and its UNAIDS region.

The headline result implies that higher income inequality is associated with higher excess mortality. Specifically, a 25 percent decline in the U.S’s Gini inequality coefficient (a fall in pre-tax and benefits inequality from 0.58 to 0.44, around the level of New Zealand or Belgium at 0.43) would supposedly have resulted in 160,000 fewer U.S. deaths in 2020/21. In other words, an excess death count 16 percent lower.

Methodological Problems

Now, there are big problems with this methodology that should be obvious.

First, this is data without a theory of causality. The authors don’t hypothesize why a bigger income gap between rich and poor within a country (as distinct from, say, deprivation, or existing ill health, or whatever else) might lead to more excess deaths. The only theory presented is a fuzzy one that says wider income disparities somehow lower social trust and make it more politically difficult to do good policy once a pandemic hits, which in turn leads to more disease spread and thus worse rates of infection and death. Interestingly, their preferred Gini index of income inequality, sourced from the World Inequality Database, is calculated with pre-tax incomes, so implies redistributive taxes wouldn’t really help here. Presumably, then, the theory is that higher economic inequality somehow neuters non-fiscal collective action.

Second, the data presented for excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic only relates to 2020 and 2021, even though for many countries there were significant waves of COVID-19 later than that. This means the period covered is primarily pre- and early-vaccine roll-out for many countries and by no means comprehensive of the overall pandemic experience.

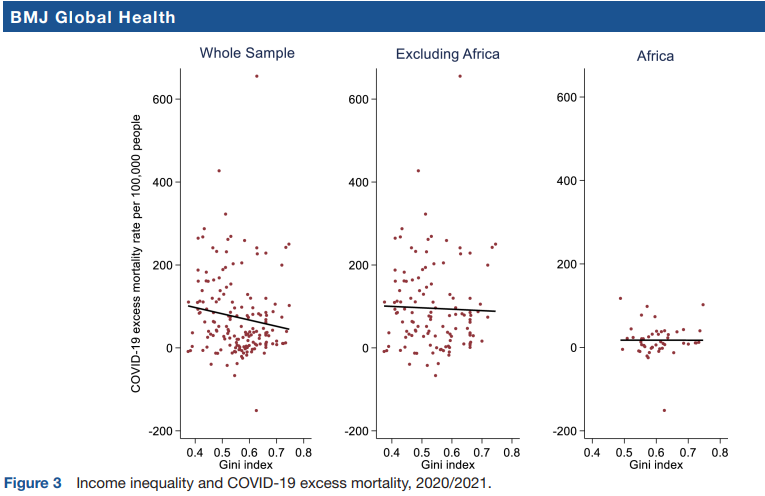

Third, the underlying paper admits that there is no basic correlation between the income inequality measure and COVID-19 excess mortality in any of their three samples (global, global without Africa, and Africa alone). In fact, in their global sample there is a very modest negative correlation, with higher income inequality associated with fewer excess deaths (see chart below). It’s only once the control variables are added in the regression framework that the positive association occurs.

An estimate’s sign flipping once controls are added isn’t a death sentence for empirical work, but it suggests getting the control variables right is extremely important. The model itself needs to make sense and we need assurance that the control variables aren’t confounded, biased, or colinear with what you want to measure.

Fourth, there are predictably major problems with the controls:

the risk of omitted variable bias. By just controlling for income group, health expenditure during the early pandemic years and region, they don’t control for a country’s age structure (% 65+), obesity/diabetes prevalence, vaccination coverage, climate/seasonality, degree of urbanization, or care-home prevalence—all factors that influenced COVID-19 mortality risk. If you leave out a factor that (1) raises COVID deaths and (2) is more common in more economically unequal countries (perhaps American obesity), the regression may mistakenly credit that factor’s effect to income inequality, making the Gini coefficient’s estimated impact larger than the real, isolated effect.

In the paper’s own loose theory of pandemic outcomes, for example, higher inequality drives worse outcomes through lack of social trust. But there are legion potential confounds here. Homogeneity in a country’s ethnic demographics, for instance, has long been thought to cause, or at least correlate with, higher social trust within a country (see, e.g., this Pew Report). And, other things given, incomes might be more equal in more homogenous societies too. So, even accepting the theory of excess mortality through the social trust channel, by failing to control for demographic composition, the paper likely misattributes low social trust to economic inequality when the real channel is a third factor: demographic heterogeneity.

the risk of endogeneity bias. The paper controls for health expenditure per capita using data from 2020/21, but health spending during 2020/21 is itself partly an outcome of the pandemic (a relationship referred to as simultaneity), so conditioning on it distorts what you want to test. It’s no surprise that countries experiencing high COVID mortality would begin spending more on healthcare than their better-faring peer countries, but a simple OLS regression is unable to partial out this bias.

The authors justify this choice by arguing that they are controlling for an omitted variable. But their broader assumption seems to be that high economic inequality makes delivering collective action in response to a pandemic more difficult. It’s tough to theorize why that would be the case for, say, non-pharmaceutical interventions, vaccines, and care-home policy, but not suddenly ramping up spending on healthcare.

they only include regional fixed effects given this is really a cross-sectional analysis, which leaves many national traits—institutions, culture, quality of vital statistics—free to further distort the Gini coefficient’s estimated effect. And the regions they do group by seem dubious at best, folding all of Western and Central Europe and North America into one group (which somehow includes Israel) while elsewhere splitting Afghanistan (Asia and Pacific region) from all of its neighbors to the North (Eastern Europe and Central Asia region). Perhaps the authors are trying to control for differences in culture or governance rather than distance, but then why group Australia with Japan or Japan with Afghanistan in Asia and Pacific? It’s hard to imagine what these groupings possibly control for in terms of the sensitivity to the pandemic.

As a result of all that, I was highly skeptical that the empirical design was capturing a real, meaningful relationship between income inequality and excess mortality during the pandemic. And even in the unlikely event that it did, what exactly does this tell us about what public policy could do to improve matters? Redistribution won’t matter—they consider pre-redistribution inequality as the driver here. So should governments risk using regulations to try to equalize market incomes in the hope that they will endure fewer deaths the next time a once-in-a-century pandemic hits because of higher social trust?

Replication Attempts

But let’s put our methodological concerns aside. We wanted to also test how robust the results themselves were. We decided to try replicating their analysis, as close to their original methodology as possible, then changing some variables to what we consider a more defensible approach (see a full comparison of results in Table 3).

We sourced data from all the same places: excess mortality estimates from the Economist, health expenditure data from the World Bank, and the Gini indices from the World Inequality database. The original paper links to this page as its source of excess mortality data, but because it’s continuously updated and no longer shows the data as it was accessed by the original researchers, we use this historic database of where the Economist’s estimates stood at the end of each month.

These data sets differ slightly, as shown in Table 1 below. Our distribution of countries is shifted toward higher excess mortality than the original paper’s. Perhaps the original paper did not regress on end of year data through 2021 (it makes sense that excess mortality would rise gradually as the pandemic continued raging), or estimates may have been revised upward since the paper’s publication. We also capture data for 20 additional countries, though it’s not clear which countries specifically were not included in the original work.

Perhaps because of this difference, we could not replicate the original paper’s results in our own regression analysis. They report a highly significant 246 more deaths per 100,000 with a 1-unit increase in the Gini index (moving from a perfectly equal income distribution to a perfectly unequal one), but we find no significant effect (driven both by our lower point estimate of 76 and a higher standard error, as shown in Table 3, column I in endnotes). To the extent there was a statistically significant effect in the first paper, then, it was sensitive to the unrevised data used.

Because of the simultaneity risk discussed above, we ran another regression changing the healthcare control to pre-pandemic health spending from 2019 as a control for preparedness (Table 3, column II in endnotes). Doing so does not change any of the estimates by greater than one standard error, meaning statistically, the models really aren’t distinguishable from one another.

More importantly, with complete data now available, there’s now no need to limit ourselves to only excess deaths in the first year and a half of the pandemic. Replicating the analysis but making excess mortality from 2020 through the end of 2023 the dependent variable, the purported effect of income inequality using their methodology shrinks down to a negative point estimate of -65 (Table 3, column IV in endnotes). To be clear, this still is not a statistically significant result, so we have no reason to believe income inequality has any meaningful effect on pandemic mortality at all. But this suggests that if there is a relationship, it’s most likely negative for the pandemic as a whole: higher inequality is associated with lower excess deaths.

As a final check, we examined how using pre- vs post-tax Gini indices of income inequality affected the results too. In this specification, we limit the regression only to OECD countries. We also removed the indicator variables for UNAIDS regions and World Bank income designations (since there would be too few countries in the OECD outside the Upper income and Western and central Europe and North America groups for reliable results). Switching from pre- to post-tax Gini indices does not significantly change the result, but again the point estimate on the inequality variable is negative (estimates of -273.6 on pre-tax data and -273.8 on post-tax data). Table 4 (see endnotes) breaks out these results fully, and as in all other regressions, the effect of income inequality is not statistically significant.

The long and short is that their apparent positive results are not robust either to revised data for the years they examined, nor other regressions tinkering with both control variables or examining excess deaths through 2023.

Other “Evidence”

If you haven’t caught on yet, we are highly skeptical about both the methodology and interpretations of this report, to put it lightly. Other supporting evidence in the paper hardly helps allay our fears.

The authors go on to say that “[t]he Council analysis contributes to a growing body of research that demonstrates an association between income inequality and COVID-19 mortality.” What is this research? Their endnotes show a few similarly flawed cross-country regressions, a study of the first 30 days (!) after a country is hit with the virus, and a correlation between the Gini coefficient of individual U.S. states and mortality rates from COVID-19…but only for 2020.

As a final gut check, we dug into the OECD numbers just to see if there was any headline indication that more income inequality was strongly associated with worse pandemic outcomes across countries. Using the Gini coefficient (post taxes and transfers) as a better measure of lived experience inequality, we mapped it against excess mortality for the whole period January 2020-December 2023.

No correlation.

Maybe this just isn’t the best inequality measure? Let’s look at the income share of the top 10 percent of income earners as the inequality metric instead.

Again, nothing.

But maybe it’s just all the redistribution; the degree of social spending (cash and benefits-in-kind from public services, or indeed cash benefits alone) that is flattering these figures? Well, relative to GDP, there’s no correlation between either social spending or cash benefit spending before the pandemic and excess mortality during the pandemic either.

What about that evidence of a positive correlation between economic inequality and COVID-19 mortality among U.S. states? Well, the pandemic didn’t end in 2020, which made me suspicious of this being the period examined.

And sure enough, for 2021, 2022 and 2023, the R-squared on a simple regression of COVID-19 mortality on state Gini coefficients falls from 0.28 (my replication was higher than their 0.25) to 0.1 in 2021 and 2022 and then 0 in 2023.

What’s more, the 2020 results themselves are highly sensitive to a few states driving the results. New York is very unequal in terms of income and was hit early and hard by the pandemic given its global interconnectedness and population density. Surrounding states like Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Jersey, with above average income inequality, were hit hard too. Take those plus the most remote states that weren’t hit much at all in 2020 out of the sample, and the R-squared for remaining states falls to 0.1 again.

Now, obviously, you can be guilty of p-hacking with this sort of thing, but the point stands that there’s a significant confound here. The virus arrived first in certain states with among the highest income inequality and spread uncontrolled in major, high-density cities with completely susceptible populations. That sounds to me like a better explanation for New York’s high 2020 death toll than its levels of income inequality.

Conclusion

Why bother examining this in detail? Well, to a certain extent we have memory-holed how destructive the pandemic was to our lives, livelihoods and liberties. Being resilient to future pandemics is of paramount importance. But getting bogged down worrying about inequality takes focus away from actual preparation and institutional reform that could help.

Pigeonholing the conversation about pandemic resiliency into one about income inequality, based on some loose and non-replicable regressions, undergirded with no theory, and with no obvious policy implications, seems as bad a use of our energies as all those fruitless 2010s debates. But I can guarantee that next time pandemic preparedness comes up, there will be people and journalists citing this UN report as gospel to claim that reducing inequality is crucial to better handling the next global pandemic.