In 1986, Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler asked 107 people about a number of hypothetical pricing decisions and whether they were fair or unfair.

In one question, a hardware store had been selling snow shovels for $15. The morning after a large snowstorm, the store had raised the price to $20, in light of demand soaring due to the snow dump.

As many as 82 percent of respondents considered this price increase to be unfair.

Across the full range of surveyed scenarios, in fact, the economists concluded that while the public seemed comfortable with businesses changing prices to protect their existing profit-levels from supply shocks, and were even comfortable with businesses not cutting prices when their costs fell, they were asymmetrically opposed to price rises that were driven initially by excess demand (i.e. temporary shortages of products).

I’ve thought a lot about this result, and how it affects business pricing decisions and public policy.

This perception of unfairness in regards demand-driven price rises is clearly a big reason why major stores and existing sellers embrace rationing or shortages rather than raising prices when emergencies hit. After COVID-19’s onset, the economists Luis Cabral and Lei Xu found that facemask prices rose by a factor of 2.4 on Amazon marketplace. Yet sellers who had been on the platform since 2019 increased their prices by just 57 percent relative to 2019 prices, whereas new sellers were able to sell at 178 percent the typical 2019 price. That suggests existing suppliers are bound by a reputational constraint from increasing prices as aggressively in a crisis, perhaps due to the repeat nature of their transactions.

This consumer fairness axiom animates the public’s continued support for anti-price gouging legislation too. Though these laws currently differ from state to state, they effectively deter businesses from raising prices after emergencies have been declared, sometimes by explicitly capping permissible increases on affected products, and other times through vague diktats that companies must avoid “unconscionable” price increases. To greater or lesser extents, all deter even small or new suppliers from serving the market when shortages would otherwise drive up prices.

But does a hostility to demand shock-driven price rises affect our political discourse more broadly? It may also explain the appeal of “greedflation” as the explanation for our recent burst of inflation. After all, aggregate demand, i.e. total spending, has run above trend in recent years, putting upward pressure on prices, and for certain industries, raising short-run profits significantly when supply was fixed.

Just as the public blame “gougers” for upping prices during emergencies, a massive 61 percent of U.S. adults think profit‐hunting corporations deserve “a lot” of blame for the sharp rise we’ve seen in the aggregate price level. They don’t see market prices as reflecting the relative scarcity of a product, disciplined by the forces of competition and consumers’ willingness and ability to pay (itself influenced by the money supply). Even if one accepts there has been a lot of stimulus driving higher spending power, it seems to be an instinct of many that it’s still unacceptable for firms to react to this shock by raising prices.

A Depressing New Survey

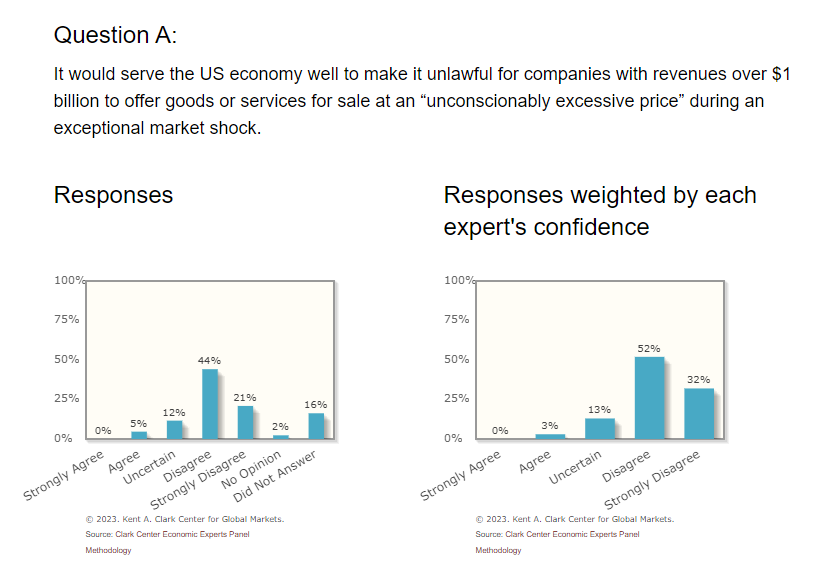

Economists generally have more positive things to say about prices adjusting to reflect new market conditions. They don’t tend to think businesses using their power to raise profit margins was the cause of our recent inflation. They also oppose anti-price gouging laws. A Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets poll of leading economists in 2022 found that, weighted by their confidence, 84 percent disagreed with Elizabeth Warren’s federal anti-price gouging proposal, for example, with just 3 percent agreeing.

Why is there such a gap between economists’ thinking and the public’s? For a long time, economists labored under the delusion that it was simply ignorance on behalf of the public. If only we could inform people about the downsides of price controls, then they wouldn’t think this way. If people knew that anti-price gouging legislation helped to prolong shortages of products by reducing the incentive for people to open their stores, or ramp up production, or fly in emergency supplies to meet demand at the new higher price, surely they would object to such legislation?

Alas, a new paper suggests this is wishful thinking.

Researchers Casey Klofstad and Joseph Uscinski, like most economists, hypothesized that disclosing the negative impacts of anti-price gouging laws would reduce support for them. Furthermore, the economists believed that if this information was advertised as reflecting the wisdom of economic experts, support would dwindle further.

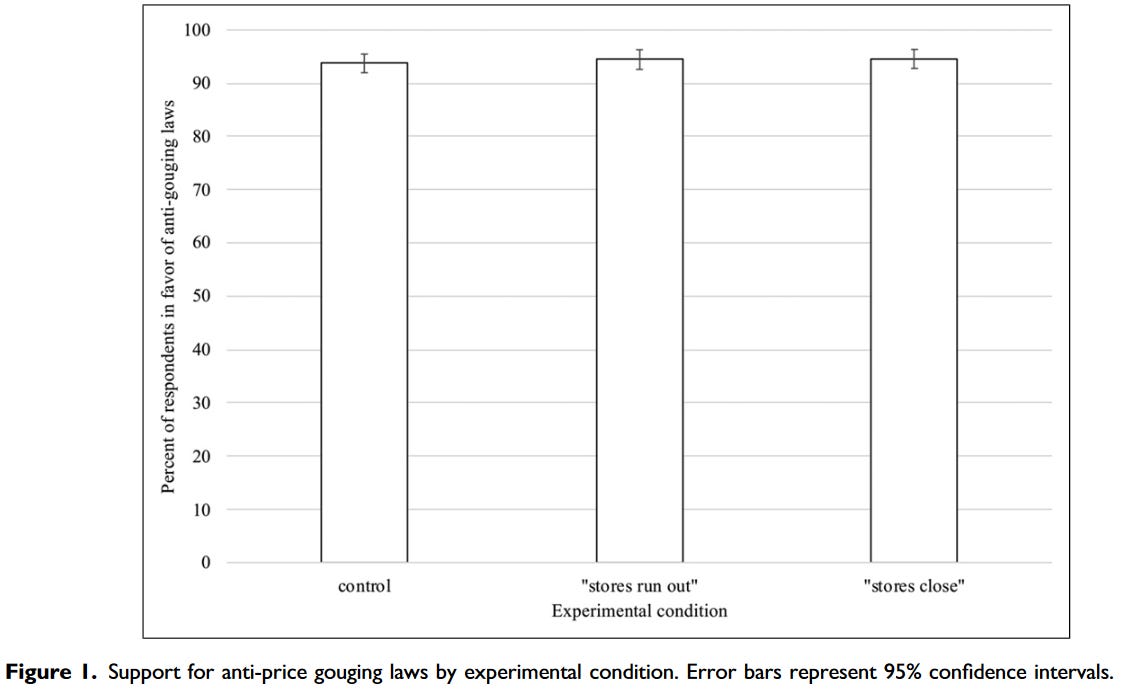

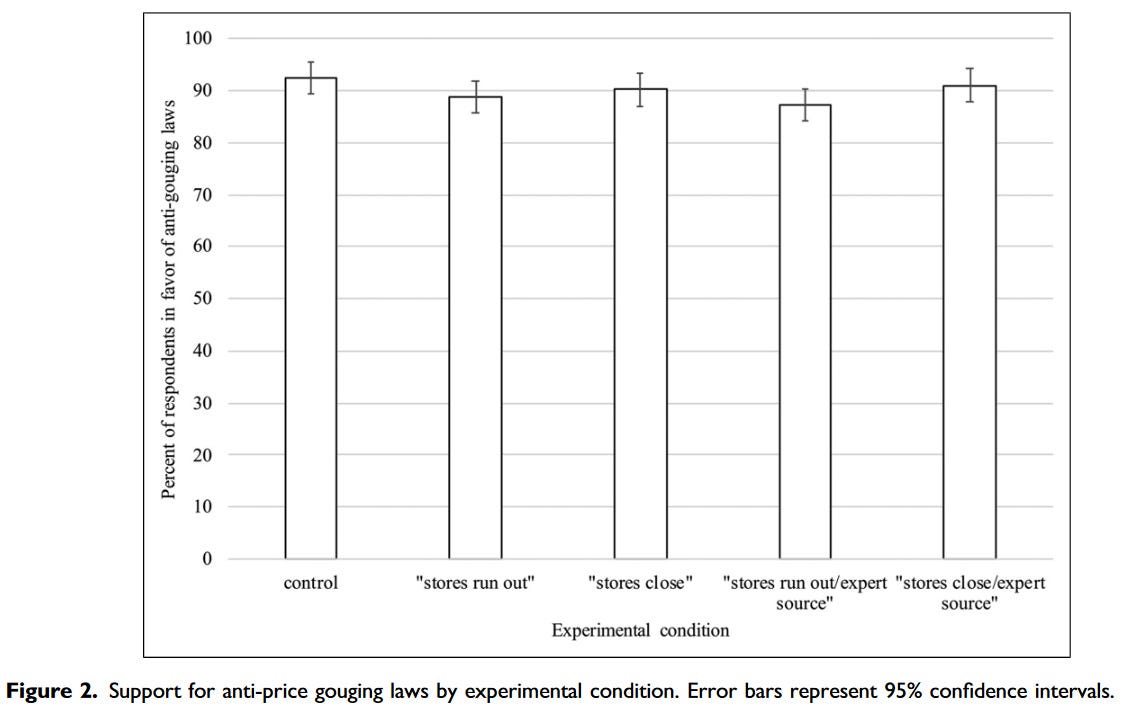

So they conducted two surveys, one in Florida and one across the US. Both randomly assigned participants to a control group or a test group. The control groups were asked if they supported a law that prosecuted price hikes after natural disasters. The test groups were asked the same question, but told that these laws might lead to store closures or goods shortages. In the nationwide survey, test group respondents were even told that “a majority of economic experts agree” about these downsides.

After adjusting for demographic differences in the data, the paper found that the public were unmoved by the extra information. They still overwhelmingly favored anti-price gouging laws, regardless of the stated downsides. The economists’ hypothesis was wrong.

For Florida, over 90 percent of respondents backed anti-price gouging laws in all scenarios, brushing aside the potential negative consequences.

Nationwide, although there was some sensitivity in support to the idea stores might run out of the goods, the effect wasn’t huge. Overall, this survey reinforced a resounding preference for anti-price gouging laws, with more than 80 percent of respondents endorsing them, undeterred by warnings attributed to expert sources.

Now, is this just because the scenarios are predicated on emergencies or natural disasters? Maybe. As Rory Sutherland writes in this week’s Spectator, people might have found peace with Uber surge-pricing in general, but when the algorithm raised prices by 400 per cent during a terrorist attack in Sydney, the company was still widely excoriated for exploiting others’ fortunes.

But the greedflation example suggests that maybe this thinking applies in non-crisis times too. A large segment of the public just seems to think that it is immoral for firms to raise prices when the initial trigger is a demand increase, as opposed to when their has been a supply or cost shock.

New Regulation of Dynamic Pricing?

Adding to the intensity of this debate is the recent breathless panic about the spread of dynamic, or real-time, pricing. Algorithmic technologies mean that more industries, including pubs and bars, bowling alleys, and ticket platforms for pop concerts, are now experimenting with charging more or less based on demand levels.

Economists would think: let businesses be free to innovate around pricing!

It’s obvious that real-time pricing can have consumer benefits on two-sided platforms like Uber, where a surge price incentivizes more driver supply by encouraging more vehicles onto the road, reducing wait times during busy periods by mitigating shortages.

But dynamic pricing can also help ration fixed capacity in ways beneficial to consumers in the longer-term too. Think about how dynamic airline pricing for seats on planes, by raising the profitability of the industry, encouraged new entry from low-cost budget airlines, while broadening access to poorer people with low prices at off-peak rates. Similar logic applies to hotels, gigs by artists and more. If pricing innovation raises profits, it encourages more supply in the longer-term.

Yet major newspapers and consumer groups have been pushing a narrative that dynamic pricing is inherently anti-customer, ripping people off by charging more “for the same product.” Their protestations hark back to the concept of a “fair price,” devoid of considering the changing market context. It reflects opposition to demand-driven price increases.

As I wrote for The Times last week, this line of thinking ignores the downsides that demand-invariant prices bring: long lines, waits and shortages at peak times; underutilization in off peak periods and wasted products; black markets when people are willing to pay much more than the price set; and less accessibility for the poor, who could otherwise access goods in quieter periods.

Yes, businesses have to weigh the effects of all this on their profitability against the strength of their customers’ preferences for price certainty and how sharply volatile prices might affect their brand as a firm. But there’s no one-size-fits-all answer.

No doubt some of the customer angst as dynamic pricing moves into new industries is due to a lack of familiarity with it. Surge pricing for a pint? Really? Many businesses have just engaged in bad marketing too. Pubs charging 20p extra for a drink in the UK during peak hours are getting abuse; those running Happy Hours are not.

But it’s certainly true that, for certain repeat transactions, consumers want clarity, or to avoid having to search from place to place reviewing ever-changing prices. As such, it’s perfectly reasonable for a business to decide, on balance, that uniform pricing is better for its profitability.

The point is: these tensions should be thrashed out in competitive markets. It’s fine if CVS, Walmart, Tesco or Boots want to keep prices stable in emergencies - they have their own brands to care about. But, equally, other firms should be free to experiment with dynamic pricing too - whether that’s real-time pricing in emergencies or adjusting rates based on lines or wait times. That’s the case against anti-price gouging laws, more broadly applied.

My worry is that the same sort of fairness axiom that leads to entrenched anti-price gouging laws could lead to the call for severe restrictions on the use of dynamic pricing too. Already major newspapers and consumer rights groups have urged regulatory agencies to step in and set parameters. Ironically, had such regulations prevented Uber’s surge pricing or airline’s dynamic pricing, it would have been customers who lost out.

Isn't the fact that economists think differently to the public proof itself that education and thinking on these matters does change your mind? Unless economists all self-select from a pool with different ethical foundations to most other people then they would have had the view of the typical non-economist if they hadn't chosen to pursue that education and career path.

Perhaps the depressing part is the amount of immersion in thinking in that way that is needed to see the problem differently, not that it cannot be done.

These results may not be as disheartening as painted. Human hard-wired ethical intuitions developed in actual zero-sum circumstances in which profiting from the misfortune of others would NOT benefit others. They may not apply when scarcity pricing can be reasonably seen as mitigating the scarcity.